The Games of the XXXIII Olympiad officially open tomorrow. Men's basketball starts on Saturday and the wrestling competitions start August 5. These used to be highly anticipated events and perhaps still are.

But, as a source of national pride, the Olympics are not what they used to be, even though the Games still attract most of the world's top athletes.

One of the best was Dan Gable, who was not only one of the greatest wrestlers in history, he is also one of the top wrestling coaches ever.

Gable won the freestyle wrestling gold medal at the 1972 Munich Olympics. As a coach, he was 355-21-1 as the head wrestling coach at University of Iowa. Gable also coached 3 USA Olympic teams.

"Gold medals aren't really made of gold," said Gable. "They're made of sweat, determination, and a hard-to-find alloy called guts."

Gable's approach to getting the best out of his wrestlers was simple:

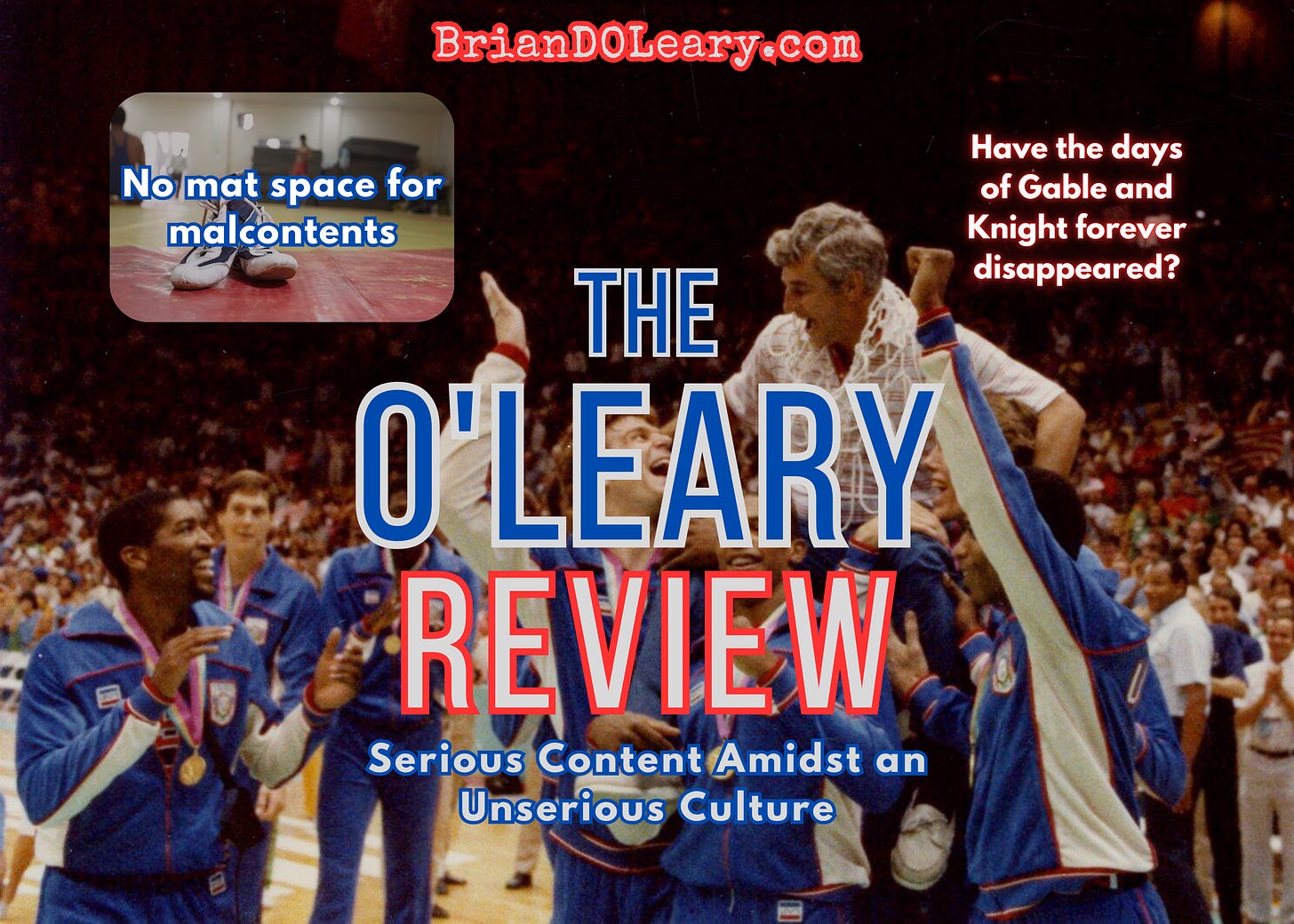

"There is no mat space for malcontents or dissenters. One must neither celebrate too insanely when he wins or sulk when he loses. He accepts victory professionally and humbly. He hates defeat, but makes no poor display of it."

While the original purpose for the Games of the Olympiad was man vs. man — individual competitors participating for both themselves and their country, team sports eventually creeped in. Men's Basketball evolved as the pinnacle of team sports in the Olympics.

For the Los Angeles Games in 1984, the Americans fielded their best "super team" up until that point, but the players were all still amateur athletes.

Forty years later, gone are the days of coaches like Gable and Bob Knight — who directed the 1984 basketball squad.

The "real" super teams started in 1992 with the "Dream Team" in Barcelona. These days, it is all professional and participation is generally transactional — another paycheck and a way to boost endorsement dollars.

Furthermore, for Paris 2024, pro basketball's Archangel of the Left, Steve Kerr, is at the helm of the U.S. hoops team. Playing for him are also several guardian angels of progressivism.

It's a different world.

In May 1982, Indiana University's Knight was voted in by a committee to serve as the head coach of the 1984 team. He said that from the day he was chosen, "there wasn't a day that passed without some aspect or detail of planning for the Olympics coming up in my mind." Such is nary a concern for the modern-day Olympian.

It was important, however, for Knight … and for the country. We were, after all, in the midst of the Cold War and the Olympics were seen as another in a series of battles for the soul of Western Civilization. The stakes were high.

"There has to be a rapport between coaches and players," Knight told the team, "a feeling for one another, a combined effort toward an eventual goal that on the night of August 10 each one of you will be standing on a platform, with the national anthem being played and a gold medal around your neck."

Knight required sacrifice. "I've got some things to ask you," he concluded. "I want to find out some things about you. We've got a lot of things we have to do to win a gold medal."

Knight also invoked the toughness and discipline required on the wrestling mat with that 1984 team. He brought in Doug Blubaugh to speak with the team. Coach Blubaugh was Indiana's wrestling coach at the time and had won the freestyle wrestling gold in 1960 at Rome in the 161-pound class.

Knight took a picture of Blubaugh's gold medal and gave every player on the basketball team a 3 x 5 photo of it to keep in their pockets "until the real thing is yours." He also gave them each an 8 x 10 copy of the gold. "I want this over your bed wherever you sleep between now and then."

Knight said of one player's commitment to the team and his nation, "The guy was amazing. Whatever was necessary to do, he could do… He didn't play much more than half the time in Olympic games, but when he was on the bench he rooted like hell for the guys who were playing."

Some end of the bench scrub on that U.S. Olympic team? Not exactly.

Knight was talking about Michael Jordan, the fellow Knight considered the best basketball player in history. The "best player was Jordan," Knight explained. "To me there's no contest."

Representing the U.S. this summer in Paris appears to be a good lot of malcontents and dissenters. Across all sports, there are plenty of today's Olympians who couldn't last under a patriot like Knight.

Attitudes that Gable wouldn't tolerate are now roundly accepted and even championed.

There is little doubt that the U.S. contingent will still rack up a large medal count. But it's not the same.

Quinn Buckner, the captain of the 1976 gold medal winning basketball team said:

"I wanted to play on the Olympic team more than I wanted to play professional basketball. After being out of the country, having been to Eastern bloc countries, I really wanted to play in the Olympics. I know it sounds corny; people razz you about it. But there's nothing like representing America. When the opportunity's there, you've got to savor it. It is that special."

Reflect.

When malcontents are sent on your behalf, whether to Washington or Paris, and they do not align with your values — and display attitudes and behaviors openly hostile to your heroes, traditions, and culture — wherefore the obligation to support them?

Is this nation now so entirely dissimilar from that bold and confident one this correspondent remembers from his youth of four decades ago?

Consider.

Tradition once mattered in America. It was a country bounded by its heritage and its heroes and its past. An America for Americans.

Yet by his endorsement today, it seems Coach Kerr dissents from such tradition, preferring by proxy that we become "unburdened by what has been."

Not everything of ours makes it over here to Substack. For regular updates — emails, podcasts, and the like — and our latest free bonus, make sure to sign up for our mailing list at briandoleary.com/letter