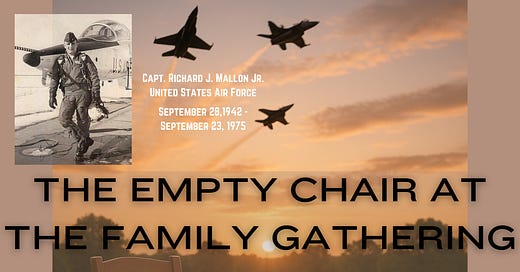

Captain Richard J. Mallon Jr. came back home to Portland, Oregon on a cold April day in 1989, nineteen years after his F-105G Thunderchief was shot down over North Viet Nam. By then, his children had grown up without him. His father—my dad’s Uncle Joe—had aged beyond his years, and our sprawling Irish clan in the Portland area learned to navigate the loss with that odd mixture of pride and grief that marks those families who have paid the ultimate price.

My family called him Rich, while his friends from school new him as Dick. In the extended family, there were always several people with the same few names, so the family shorthand reduced otherwise complex relationships to digestible morsels.

I never met Captain Mallon. He went missing several years before I was born.

Rich was my father's older cousin, and as far as I could tell, his #1 hero. But his cousin’s fate wore on my dad. While I admired the U. S. military as a boy, my dad made it clear that there would be problems between us if I ever were to join up myself.

My late father, a man not prone to sentimentality, spoke of his cousin with the reverence reserved for saints. That wasn’t often, but, on occasion, he’d open up.

Rich Mallon was twenty-seven when his plane went down over a Vietnamese jungle. He was considered missing in action (M.I.A.), though likely—but unofficially—presumed dead. His family would not know this with certainty until 1989.

Mallon had already completed more than one hundred combat missions during two tours of duty in Southeast Asia. These numbers matter because they speak to something our modern culture has largely forgotten: the concept of duty that transcends personal ambition or comfort.

On January 28, 1970, Captain Mallon was flying escort for a reconnaissance mission near the Laotian border when enemy ground fire damaged his aircraft. He ejected successfully and was seen landing safely, but search and rescue operations could not reach him in the enemy-controlled territory.

That was the last any American saw of Rich Mallon alive. His electronics warfare officer, Captain Robert J. Panek, was also lost in the incident.

The official tally from Vietnam says that “the conflict” claimed 58,281 American lives. Rich was one number in that staggering total, but numbers tell us nothing about the grief that settles into those households when the telegram arrived.

My grandparents, my father, and his sisters occasionally spoke of that period, but I didn’t hear a whole lot of it, honestly. We Irish were supposed to be the strong, silent types, after all. However, the not knowing, the hoping, and the gradual acceptance can ultimately transform denial into a different kind of faith entirely.

Outside of the family, what followed was a masterclass in the bureaucratic indifference that characterized much of America's handling of Vietnam's aftermath. Mallon's remains were returned to U. S. custody in December 1988 as part of a repatriation by the Vietnamese government.

The Central Identification Laboratory-Hawaii identified his remains in April 1989. By then, the Cold War was nearing its end, and the American government was more interested in looking forward than backward.

September 23, 1975, was given as Mallon’s presumed date of death. So, what exactly happened?

Well, that is a horrible mental exercise that I choose not to think too much about.

The funeral took place at the University of Portland chapel, followed by burial at Willamette National Cemetery with full military honors. As a 12-year-old boy, I was there along with my entire family.

Four jets from McChord Air Force Base flew overhead in missing man formation, with one aircraft breaking ranks to soar alone into the sky. There was a 21-gun salute.

His daughter Carolyn and son Brian had waited nineteen years to bury their father.

I think often about those nineteen years. What it must have meant to live in limbo, to hope against hope, to maintain faith when evidence suggested faith was foolishness. This was before the internet, before social media, before the instant gratification that now defines American expectations.

For two decades, our family, especially the cousins and aunts and uncles I knew that were closest to him, lived with uncertainty in a way that is foreign to most Americans today.

At one point, America crossed the line between republic and empire, but I don’t know exactly when that was. It is now apparent that our foreign commitments are unsustainable and have been for some time.

But here is what a lot of us, myself included, have trouble grasping: sometimes young men go anyway. Not because they believe in the grand strategies hatched in Washington, but because they believe in something more fundamental—duty, honor, and the notion that some principles are worth defending even when the mission is unclear.

Richard J. Mallon flew more than one hundred combat missions not because he was a warmonger or an imperialist, but because he was a professional who understood that saying yes to military service means saying yes to missions you might not choose for yourself. This is a concept that our current political culture, with its emphasis on personal “freedom” and individual “choice,” struggles to comprehend.

As I write this in 2025, it strikes me that Rich Mallon’s sacrifice carries lessons our current generation desperately needs to understand.

The modern Memorial Day has devolved into a three-day weekend that marks the unofficial beginning of summer. Barbecues, beach trips, and retail sales have replaced the solemn remembrance that the holiday was designed to commemorate. This transformation reflects a broader cultural amnesia about the costs of the freedoms we take for granted.

Captain Mallon represents something that transcends politics: the willingness to serve something larger than oneself. Whether you supported the Vietnam War or opposed it, whether you believe America's foreign policy serves noble purposes or imperial ambitions, young men like Rich Mallon made a choice to place duty above personal comfort.

As of this Memorial Day, American military personnel are deployed around the world in conflicts and commitments that most Americans could not locate on a map. The technology has changed—drones have replaced some fighter jets and cyber warfare has joined conventional combat—but the fundamental dynamic remains the same. Young Americans continue to write checks to the nation that may be cashed with their lives.

My cousin’s story reminds us that freedom is not free, that a nation requires defenders, and that some prices are paid by families like mine while others enjoy the benefits without shouldering the costs. His nineteen-year journey home teaches us patience, faith, and the importance of remembering those who serve.

Think of that empty chair sitting next to you next time you barbecue with friends and family. It represents Rich and others like him who answered when called and never made it home for the reunion.

Today, while others fire up grills and knock back Budweisers, I encourage Americans to remember Captain Richard J. Mallon, Jr. and the thousands like him whose sacrifice makes our comfort possible.

Remember that freedom requires defenders, that a democracy demands more than voters, and that some young Americans continue to pay prices that others are unwilling or unable to pay themselves.

The least we can do is remember their names.