I grew up in Portland, Oregon and enjoyed almost every aspect of my childhood and living there. I was rooted in the city. My family has been there since the 19th century.

I never anticipated leaving, and even though I moved away some years ago, there is no mistake in my mind that I am and forever will be a Portlander and—more importantly—an Oregonian.

Nobody can ever take that away from me. Not a senator who forsakes constituents for party dictates, not a corrupt and creepy mayor, and never a gender-bending governor. Sadly, none of these examples are limited to single instances.

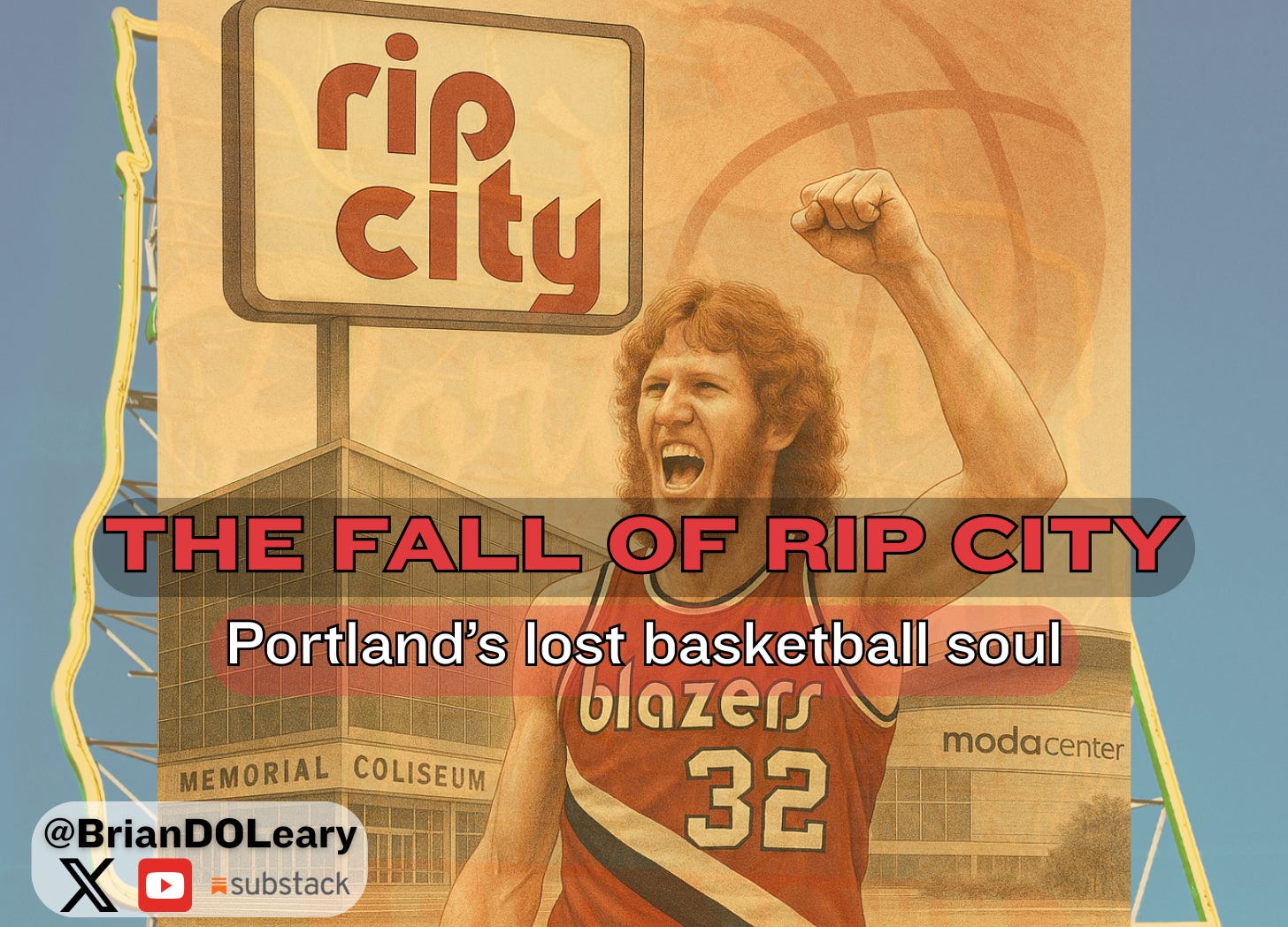

As far as Portland goes, I arrived on the scene during an interesting time in the city’s evolution. When I was but a wee infant, the NBA’s Trail Blazers won their first and, so far, only World Championship.

That 1977 victory defined not only my youth, but a good portion of the lives for generations of Oregonians—born well-before and soon after the Blazers won the title. No longer were we a forgotten outpost amidst the forests of a distant land.

We were winners. We mattered.

The famous image of Bill Walton pumping his fist skyward proved it.

The championship season was a coming-of-age of sorts for Portlanders and their city. For once, we had established a winning culture, and things were beginning to go in a positive direction. It was a period we looked back upon with great joy and admiration.

The Trail Blazers—from the players, coaches, and executives to the announcers and even the beat writers and columnists covering the team—were woven into Portland’s cultural fabric. Sadly, this is no longer the case. If people still believe it, they delude themselves.

Nevertheless, sports fandom will always have its place in the hearts of most Americans. Blazer fans, of course, still exist, and in perhaps bigger numbers than they did in the franchise’s salad days, but to say the Trail Blazers are still a major cultural component within the Rose City would be a lie or at the very least, a gross misinterpretation of the truth.

So, the news... The estate of Paul G. Allen (d. 2018) officially put the Portland Trail Blazers up for sale, announcing that all proceeds will go to philanthropic efforts as directed in Allen’s will, while explicitly stating that the Seattle Seahawks and the estate’s 25% stake in the Seattle Sounders are not currently for sale. The announcement came this week, though rumors have swirled for months.

For many years, the NBA was my favorite league in pro sports. Playing no small part in my fandom was that we had the Blazers, Portland’s only major pro sports franchise. To this day, the Blazers are the only game in town when it comes to big-time pro sports.

There are those contrarians who will naturally chime in with, “But the Timbers! And the Thorns! And the Pickles!” First, these folks need help but will likely never seek it. Next, they must take a pill. Then, hopefully, get a grip on reality.

At one point, we were close to getting the NHL’s Pittsburgh Penguins, but Mario Lemieux came to the rescue of the fans in the Steel City and the franchise remains in western Pennsylvania to this day.

The NFL’s peripatetic Raiders were rumored to move to Portland at one point, but that also fell through. It would have been a fleeting relationship anyway. Who knows how long the Davis family would have been attached to just another city west of the Rockies?

In baseball, we had the Portland Beavers for nearly 100 years—though not all consecutive. For most of the history of the Beavers, it was a Triple-A franchise (or its equivalent level). Great ball and a lot of great players, but it was never the big leagues.

Growing up, baseball was my favorite, but I had no real fondness for the American League or the National League as entities like I did with the enterprise known as the NBA. Mostly I loved the history of baseball, playing it, and nearly everything else about the sport. Portland was a great baseball town at one point, too, and that culture only increased my love for the National Pastime.

Pro football was huge for me also. I was like a pig in slop as a seven or eight-year-old when the USFL came to Portland in the form of the Breakers—formerly of Boston and then New Orleans. That ended.

But basketball was always accessible. I can’t imagine it was anywhere close to Indiana-level obsession when it came down to it, but Portland’s basketball heritage is nonetheless outstanding, and it outpaces other cities of its size for legitimate basketball stars.

Most people I knew had a basket or “goal” in their yard or driveway. Everyone shot. Even if it was NERF hoops in the bedroom or wadding up notebook paper and shooting those balls into a wastebasket. You’d almost always see a kid at the park shooting hoops by himself or a pickup game going on. The culture was infectious.

And we loved the Blazers.

Furthermore, the NBA had authentic superstars. Way more per capita than in the other sports. In the 1980s and 90s, every game was also important. League-wide, none of the stars took time off during the season like they do now.

There were no rest days, unless the guy couldn’t walk. Even then, most NBA players would at least try to lace up their sneakers.

On cable television, you could see, on most any given night, the Chicago Bulls with Michael Jordan on WGN or the Atlanta Hawks with Dominique Wilkins on TBS. To be honest, I probably watched more Hawks and Bulls games on TV than I did the Trail Blazers.

Jordan was nothing short of the greatest sportsman of a generation and 'Nique introduced us to the finer points of the windmill dunk in the context of the half-court offense.

National games on various networks were generally appointment television.

Blazer home games were usually only available on closed-circuit TV. People often went to movie theaters to watch important games amongst other rabid Blazer fans.

Still, we could always listen to the Blazers on the radio (KGW or KEX), and we read Dwight Jaynes and others in the morning’s Oregonian telling us what happened. Most of the Blazer road games on local television were tape-delayed unless they were in the Pacific or Mountain time zones.

It was a major cultural event in town if the Blazers were tapped to be on national television. It happened rarely, even when they made their championship runs in the late 80s and early 90s. On CBS and then NBC, for those of us who rarely got a ticket to the sold-out Memorial Coliseum, we could occasionally get a glimpse of our home team in those iconic, crisp white uniforms with the scarlet and black sash, and all the fans cheering—nay, going berserk—for our ball club. Our ball club.

That was important.

There was something almost religious about radio announcer Bill Schonely’s voice coming through the radio. “Good evening, basketball fans, wherever you may be,” he would intone, as though summoning the faithful to prayer.

Schonely created the now famous “Rip City” phrase during a broadcast in 1970, one that would become the shorthand for an entire community’s identity. When a player made a crucial shot, Schonely would exclaim “Rip City, Alright!” and households across Oregon erupted in cheers.

I remember when I was 13 years old, the Blazers were making a run at the NBA Finals. The energy in town was palpable. My Babe Ruth team was playing in Southeast Portland, and I was leading off second base when the catcher from the other team ripped off his helmet, stood in front of home plate, and announced to everybody on the field and both dugouts that the Blazers had just won and WE were going to the Finals, the first time Portland reached the Finals since 1977.

Cheers from the fans. High-fives all around and within both dugouts.

The fellow put his mask back on, squatted behind home plate, and the game continued. I’m not sure if the umpire ever called, “Time!” or not.

Strange episode, for sure. The catcher may have gotten the news from one of the parents behind the backstop or he could have even eavesdropped on the several boomboxes and transistor radios in the bleachers.

It wasn’t uncommon for parents to listen to the dulcet tones of “The Schonz” as their sons played baseball in front of them. It was just what people did in Portland.

Two years later, I had the great fortune of attending Game Three of the NBA Finals at the Memorial Coliseum against Michael Jordan and his Bulls. Portland lost, but it was an amazing experience to be at the NBA Finals amongst those fans. Something I’ll never forget.

These weren’t mere sporting events. They were civic communion. When Clyde Drexler glided through the air, his flight seemed to lift the entire city. When Jerome Kersey crashed the boards with reckless abandon, his toughness reflected Portland’s once common blue-collar soul. When Terry Porter orchestrated the offense with precision passes and clutch shooting, his steadiness represented the best of us.

To understand Portland’s basketball obsession, one must understand what happened in 1977. The Trail Blazers, a young expansion franchise that had never so much as reached the playoffs, shocked the basketball world by defeating the mighty Philadelphia 76ers in six games. Bill Walton, with his flowing mane of red hair and transcendent passing ability, was the centerpiece of Jack Ramsay’s beautiful, team-oriented system.

The final game of that championship series was a basketball drama worthy of Shakespeare. On June 5, 1977, Portland overcame the heroics of Julius Erving, who scored 40 points, and George McGinnis, who added 28. Walton delivered a performance for the ages: 20 points, 23 rebounds, seven assists, and eight blocks. When the final buzzer sounded on Portland’s 109-107 victory, pandemonium erupted.

On occasion, you could sometimes revisit the magic with a kid or two whose parents somehow had Game 6 on videotape. Those Finals tapes are now archived on YouTube and elsewhere.

As Walton later described it to Sports Illustrated: “The people knocked down the railings, they knocked down the police, they just kept coming... they were ripping at our clothes, ripping at our hair, and I just started throwing my sweatbands, my wristbands, my headband... my jersey into the stands.”

It was pure, untamed joy.

Jack Ramsay, that brilliant basketball mind of baldpate and plaid pants, crafted something special with that squad. It was a team that reflected the values of Oregonians, one that played with an unselfishness and intelligence that captured the region’s spirit.

It wasn’t star power. Walton and, perhaps, Maurice Lucas were the only archetypical “stars” on that team.

It became star creation as the team executed Ramsay’s system on the floor and as a mutual respect and belief developed between the players and a grateful Blazer Nation.

When future Hall of Famer Rick Adelman took over as head coach in 1989, he inherited a team built around Clyde Drexler’s otherworldly athletic gifts. The 1990 and 1992 Finals runs were Oregon’s reentry into basketball relevance.

We believed again.

Those teams—with Drexler, Porter, Kersey, Buck Williams, Kevin Duckworth, and sixth-man Cliff Robinson—were loaded, but also played with a style that was both beautiful and tough. The Memorial Coliseum shook with noise. My late father, who fondly remembered attending that Championship-clinching game in '77, once told me he could feel the building physically moving beneath his feet.

Jaynes wrote in the Oregonian after the 1990 Western Conference Finals victory: “Portland has reclaimed its basketball soul. The ghosts of 1977 no longer haunt us—they inspire us.”

We believed a second championship was our birthright.

It never came.

Jordan and the Bulls denied us, as did Isiah and the Pistons a couple years before. But even in those defeats, there was dignity because the entire community rode those waves together.

The wins belonged to us all. So did the losses.

David Halberstam’s masterful book, The Breaks of the Game, documents the 1979-1980 NBA season from a Blazers’ perspective. Reading it now is like examining archaeological evidence of a lost civilization. Halberstam captured a team and league in transition—the championship glow fading, the business side ascending.

The book opens with the painful aftermath of the 1978 playoff loss to Seattle, when Bill Walton’s foot injury derailed Portland’s dynasty before it truly began. Halberstam wrote: “The mood in Portland was one of mourning. They had lost more than a playoff series; they had lost a dream.”

That sentence encapsulates what made the Blazers different. Losing wasn’t about standings or statistics. It was about community heartbreak.

When doctors told Walton his navicular bone was fractured, it wasn’t just his foot that broke—it was Portland’s collective heart.

Halberstam captured something else essential about Portland basketball: It was never just about the game on the hardwood. It was about identity and who we were as Oregonians.

When speaking of the 1977 team, Halberstam noted, “In a region that was used to being overlooked, they had brought national recognition and respect.”

We can never get that back.

Certainly, ballplayers of today earn more money and, frankly, they might even be more athletic and more skilled than they have ever been.

But the NBA is now a shell of its former self. The league’s administration is awful. The star power is virtually gone, and the gameplay is completely uninteresting.

Three-pointers and breakaway dunks with uncontested rebounds and cheap put-backs is what the game has largely turned into. For those who wanted to listen—and virtually nobody did—I predicted this years ago.

After the “Bubble” fiasco in Orlando in 2020, I hardly watch anymore. I can’t. The league, the basketball media, and many fans treated the game and its long legacy of greatness with a level of triviality that was previously unrivaled in the four major sports.

To be fair, baseball, hockey, and football weren’t exactly courageous, either, during that time.

In 1994, while pathetic for other reasons entirely, Major League Baseball still had the sense to cancel the rest of the season rather than dress itself in a skinsuit of the sport and pick up where they left off … several months later.

For the National Basketball Association, my passion is now long gone. But, for the sport of basketball, my passion remains. It’s a wonderful sport.

Today, the fallout is entirely different than the story Halberstam crafted, one that kept unfolding and was still fresh in the minds of Portlanders for at least a decade. Back then, we had hope—Portlanders, Blazer fans, and NBA enthusiasts alike.

By the end of Halberstam’s epic, Bird and Magic were on the NBA horizon. They hadn’t yet fully arrived on the scene, but things were about to change in a major way.

While the NBA of my youth was driven by Larry Bird and Magic Johnson, and to some extent Dr. J., Michael Jordan came along and took it to the stratosphere.

I wish someone like Halberstam was around to write a post-mortem of this latest era in Blazers history, but I reckon such a project will never get past the wishing stage.

And now, the Portland Trail Blazers are for sale.

A few years ago, Phil Knight offered to buy the team for roughly $2 billion. Presumably, Phil wanted to keep the tradition alive in Portland, in Oregon, and in the Pacific Northwest. He does a great job on that front with the Oregon Ducks football team, Nike, and all the rest of it, but with the Blazers, I doubt if Phil will get another crack at it or if he even wants one.

I don’t know who the next owners are going to be, but it’s going to cost billions of dollars to buy the team, probably more than Knight was willing to pony up a few short years ago.

The cruel irony is that the team’s value has skyrocketed while its cultural significance has plummeted. For instance, one of the Blazers “City Edition” uniforms paid homage to the plaid patterns of Ramsay’s wardrobe and includes a gold trophy icon at the back neck as “a proud reminder of the team’s historic 1977 Championship victory.”

They’re selling nostalgia because they have nothing else to offer.

Is it even a tradition worth keeping?

I’ve been away from Portland for the better part of the last decade, but most of my family still lives in the area like we have for generations. The original plan was to come back home someday, sooner rather than later.

We shall see. The idea becomes more in flux as time marches on. For, as Thomas Wolfe told us, you can’t go home again.

Portland has changed. The NBA has changed.

None of it particularly for the better.

Bill Schonely passed away in 2023 at age 93. His replacement on the airwaves, the monumentally underrated Brian Wheeler, died in 2024. With them went the last authentic voices of Portland basketball.

Schonely’s catchphrase “Rip City” lives on but is now corporate-approved and focus-grouped for maximum marketability. Moreover, in an ironic twist, as the branding whips up into a froth and more people hear the term, its impact has dwindled.

Rip City has become little more than curious words on a jersey or a social media hashtag for the league’s most obscure franchise.

Not that the NBA is obscure, but it—and sports in general—doesn’t move the needle as much as it once did. For that matter, it’s not even close.

The NBA I grew up with valued teamwork, ball movement, and fundamentals. Jack Ramsay built an offense where everyone touched the ball, everyone moved, and everyone mattered. Today’s game is a statistical exercise, a mathematical equation solved by eggheads using three-point percentages and other analytics.

The Memorial Coliseum, that concrete and glass marvel where I sat in awe as I took in Game 3 in 1992, is now an afterthought. The building is still there but it does little more than host major junior hockey.

The Rose Garden Arena (now with the corporate branding of “Moda Center”) is perfectly fine, I suppose, like all modern arenas. But it was designed more for luxury boxes than for 12,666 wildly passionate fans.

And like almost all sports stadia of today, with three decades under the belt, the Rose Garden is going to need a facelift and a tummy-tuck, pronto. Either that, or a new arena entirely. Both solutions come with a likely nine- to ten-figure price tag.

The late Bill Walton was not much for complaining about things, at least in the last several decades of his life. On the contrary, he was relentlessly positive.

But I wonder what Walton really thought when he saw what basketball turned into at the professional level?

Did he even recognize the game in which, from the early-70s to the mid-80s, he played a gigantic part in revolutionizing?

I doubt it. Walton was about movement, about seeing three passes ahead, about making teammates better. Today’s game is about individual brands and social media relevance.

What, if anything, resembles Dr. Jack’s beautiful system in the endless parade of today’s step-back threes and isolation plays?

When the Blazers sell—and they will sell for a record amount—it will formalize what has been true for years: The team is no longer about Portland but about business.

The passionate connection between a city and its team that existed in 1977, in 1990, even in the early 2000s, is gone.

Maybe it was inevitable. Maybe nothing that pure could last in modern sports.

But for those of us who remember the echoes of Bill Schonely’s voice crackling through the speakers of our AM radios on winter nights, ones who can tell you how the entire state held its collective breath during playoff games and recall what it felt like to have a team that belonged to us—not to hedge funds or entertainment conglomerates—something precious has been lost.

And it’s never coming back.